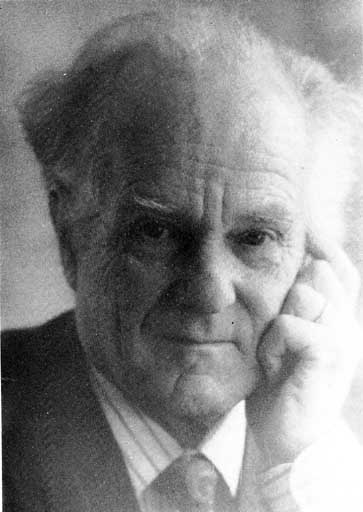

Michael Dobson (1923-1992)

A tribute written in 1993 by his friend and colleague, oboist, James Brown.

With the untimely death of Michael Dobson last December at the age of 69, we lost not only a fine musician and a good friend to many of us, but also yet another of that dwindling band of oboists, whose style, character and versatility is little known to today's younger players of the instrument. I was fortunate enough to have played alongside him for many years, and although I was never his pupil, I recognise, nevertheless, the influence that he had on me as a player. We spent thousands of hours together over the years, but before I slip into my anecdotage, I must recount a little of the chronology of his career.

With the untimely death of Michael Dobson last December at the age of 69, we lost not only a fine musician and a good friend to many of us, but also yet another of that dwindling band of oboists, whose style, character and versatility is little known to today's younger players of the instrument. I was fortunate enough to have played alongside him for many years, and although I was never his pupil, I recognise, nevertheless, the influence that he had on me as a player. We spent thousands of hours together over the years, but before I slip into my anecdotage, I must recount a little of the chronology of his career.

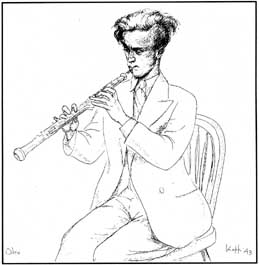

Michael was born in 1923, and being the fortunate possessor of both a good treble voice and a natural musicality, he was able at the age of seven to become a Chorister at New College, Oxford. When his voice broke, he was sent to Bryanston School in Dorset, where he started to play the oboe at the age of fourteen. There was a good tradition of music at the school, and he was able to take full advantage of this. So much so, that when he left school, he went straight to the Royal Academy of Music, and after a very short time indeed-a question of weeks, I believe - he was doing some extra work with the London Philharmonic Orchestra. It was in wartime, of course, and conditions were very different then, but in any case, he was already very disillusioned with the Academy. His lessons with Alec Whittaker-one of the great Characters of the Profession - were erratic, to say the least. There would be three or four weeks without any tuition, and then Alec would turn up as many times in one week whilst he was between tours with the L.S.O. Then he would be off again for another long period. Michael felt too, that the orchestral experience he was being given as a student was grossly inadequate, and becoming more and more frustrated with the situation, he left quite abruptly - and became the Principal Oboe of the L.P.O. at the age of 19. As I mentioned before, these really were extraordinary times during these wartime years, and Michael certainly appreciated his good fortune that so many of the younger, established players were then serving in the Forces, thus giving him such opportunities.

I first met Michael in the spring of 1945 when I was introduced to him during the interval of an L.P.O. concert in Bristol. I wish that I could tell you how impressed I was with his playing at that time, for he was still only 2l, but I was a 15 year old schoolboy, so over-whelmed by the whole event that I can only remember seeing him and not actually hearing him. Evidently he made a great impression on me, because when I had to seek some professional's advice as to the desirability of following a career as an oboist, my music master suggested that I should write to Michael to seek his opinion. To my surprise and delight, back came an exceptionally kind, helpful, informative and long letter. It consisted of five closely typed pages, crammed with all manner of information and advice. He hypothesised how he thought things might be after the war on the musical scene, he spoke of his own good fortune under the prevailing circumstances, and he spoke very critically of London's musical institutions, and in particular about the one of which he had had some personal experience. It was a marvellous letter, and I have it still. It was even the more remarkable when one considers how little free time he must have had at his disposal to do anything. You see, those first few months with the L.P.O. put him under a terrific strain. Much of the time he found himself sight-reading at the concerts works that were already long in the Orchestra's repertoire and which were virtually or completely unknown to him. Because of the exigencies of wartime travel, there was generally insufficient time left for a rehearsal, and you can imagine how exhausting this time must have been for him.

After a few years, Michael had a short leave of absence from the L.P.O., during which time he went to Paris to have a concentrated course of lessons with the distinguished teacher and player, Mystil Morel, who was also the teacher of another great oboe player, Terence MacDonagh. I like to think that Michael's great interest in good food and wine came from those weeks in Paris. Certainly, I have never met a more adventurous eater than him, and I have in my time spent countless hours on tour in his company, seeing him sample the local fare with great interest, but not with greed, for he was essentially a gourmet, not a gourmand.

When he returned to the L.P.O. after his studies in Paris, he was the proud possessor of a new Marigaux cor anglais, and after playing it in Holst's ballet music from "The Perfect Fool", Sir Adrian Boult immediately appointed him the orchestra's principal cor anglais player. So with Jock Sutcliffe as principal oboe at that time, here was indeed a strong oboe section.

After some ten years with the L.P.O., Michael left it to become a very busy member of London's pool of freelance musicians. For me, Michael was the true professional. He would play any sort of music to the best of his ability whether he liked it or not, never giving less than l00% of himself. He played for some years with the BBC's Light Music Unit, for instance, an engagement known by that wonderful cor anglais player Peter Newbury as "Appointment with Fear", as you never knew what was to be recorded until you sat down in the studio. On one occasion, we both turned up at Maida Vale Studios for a 9 am session, and by 9.25, Rossini's "Silken Ladder" overture was safely recorded, the notorious oboe part flawlessly executed by Michael.

After some ten years with the L.P.O., Michael left it to become a very busy member of London's pool of freelance musicians. For me, Michael was the true professional. He would play any sort of music to the best of his ability whether he liked it or not, never giving less than l00% of himself. He played for some years with the BBC's Light Music Unit, for instance, an engagement known by that wonderful cor anglais player Peter Newbury as "Appointment with Fear", as you never knew what was to be recorded until you sat down in the studio. On one occasion, we both turned up at Maida Vale Studios for a 9 am session, and by 9.25, Rossini's "Silken Ladder" overture was safely recorded, the notorious oboe part flawlessly executed by Michael.

In the 1960s, Michael also played in Mantovani's Light Orchestra. Several times on a long American tour that we made together with the R.P.O. in 1963, he would slip a quarter into the jukebox in the roadside coffee-shop where we had stopped, and with a look of impish glee would listen to the strains of some luscious oboe solo or other that he had recorded with him.

Michael eventually found his true playing niche in the more genteel world of the chamber orchestras, first of all in Anthony Bernard's London Chamber Orchestra, and then for several years with the London Mozart Players under Harry Blech, and in Yehudi Menuhin's (Bath) Festival Orchestra. There are a couple of recordings of him from this time that show him at his best. One is of Bach's Cantata 82, "Ich habe Genug" with Janet Baker, and the other is of Mozart's Concertone for two violins, oboe and 'cello with orchestra. Both of these were made by E.M.I. with the Menuhin Orchestra, and I find it both reprehensible and inexplicable that Michael's name is nowhere to be seen on either the record or its sleeve, in connection with these two important pieces in the oboe's repertoire. I believe that he also played the oboe d'amore in a posthumous recording of Kathleen Ferrier singing the "Qui sedes" from Bach's Mass in B Minor. Apparently the engineers were able to extract and separate the vocal part from the original recording, and they then dubbed the orchestral accompaniment on in later years, during which time thequality of recording had considerably improved. I have not actually heard this, but it would certainly be interesting to hear it.

I played second to Michael in the L.M.P. and in the M.F.O. for a dozen years at least, and one curious anecdote is worth relating. The oboes and horns of the Menuhin Orchestra were once engaged to augment the visiting Wurttemberg Chamber Orchestra (a string ensemble in those days) in Mozart's A major Violin Concerto. We turned up at the Q.E.H. for the rehearsal, were introduced to the orchestra in true German style, and when I asked the conductor, Jorg Faerber, for the music, he nearly had a fit-he had left our parts behind at his home in Heilbronn. He suggested that we should return in an hour or so whilst he had the parts sent over from the B.B.C. Library, but that was the last thing that Michael wanted to happen, as he was rehearsing and recording the Strauss Concerto that afternoon with the B.B.C.Concert Orchestra.

So with great confidence he said "Don't bother with the parts just now-we'll play it from memory". Well, fortune favours the brave, and we played the whole piece more or less immaculately without music, and at the end of each movement there was an ever greater round of applause from the string players. We were lucky, in-so-far that we had played that concerto four times recently on a Menuhin tour, and what's more, it was probably the only piece in the entire orchestral repertoire that we could have played from memory. The spin-off from this episode was that we were always invited to play with them on their subsequent visits, and in their tenth anniversary year, we went to Stuttgart and Heilbronn to play all the Brandenburg concertos with them.

Whilst Michael had been playing all this time in other people's chamber orchestras, he had been formulating plans for having his own orchestra, and it was in 1962 that he founded the Thames Chamber Orchestra at a time when the B.B.C.'s Third Programme was in its heyday. There were so many opportunities in those days for chamber ensembles and chamber orchestras, there were Bach Cantata series, baroque concerto programmes, accompanying spots for young soloists and for choirs, and the orchestra took part in many broadcasts, conducted by Michael. There were concerts too, firstly in that lovely church in Kingston on Thames, then later on the South Bank at the Q.E.H. and the Festival Hall, as well as at the Albert Hall and at many other venues. Michael worked prodigiously hard to promote and sustain the Orchestra's activities, writing his own programme notes and even printing them himself, for printing was one of his many interests and he had all the equipment for doing this sort of production.

The personnel of the T.C.O. in its early days was drawn largely from amongst Michael's closest friends in the profession, but he had a tremendous interest in the talents of the younger generation, and as the orchestra itself grew older, so the average age of its members became lower. He liked to feature their abilities whenever possible, and many of them had their first concerto experiences with the T.C.O., directed by Michael. It was a lucky accident of history that when he started the orchestra, it was in the days before the renaissance of interest in period instruments. Despite his admiration for the skill and artistry of some of its leading protagonists, Michael belonged to the school of thought that the early oboe had been improved for a very good reason, and whilst he absorbed some of the "authenticities" of phrasing and performance, had it been mandatory to play eighteenth century music on eighteenth century instruments in 1962, then the whole concept of the T.C.O. and its personnel would have been quite different.

Michael was first married to that wonderful soprano, Dorothy Bond, who died so tragically young, leaving him with their daughter Ann. Michael's second wife, Mary, whom he married in 1952 and who survives him, together with his son Richard, was very artistic and an excellent painter. They had a profession of mutual interests and a common sense of taste and style, and they respected and supported each other's talents. Amongst her other qualities, Mary is a fine cook, with Michael's interest in an adventurous cuisine, and it was always a particular delight to dine in the company of both of them. Furthermore, the value of her unfailing support for Michael in some of the darker moments of the history of the T.C.O. cannot be over estimated.

In that letter that he wrote to me in 1945, Michael said-and I quote- "When I finally got to my present job (principal oboe in the L.P.O.), they even asked me to give it up and come back to the Academy, as they thought that I should get better experience there: I am glad that I did not take their advice." Well, go back he eventually did, but this time it was to become a member of the professorial staff. And the most splendid irony of all was that, for his outstanding contribution as a long serving teacher and for his dedication to his pupils, the Royal Academy of Music bestowed on him the honour of a Fellowship.

It is fair to say that in the latter part of his career, his main musical interests became the T.C.O. and his teaching position at the Academy. Michael and Mary were by now living in Bath, and it was easily possible to continue the administration of the T.C.O.from there. He was still very much involved with a busy teaching schedule at the RAM., but whenever possible, he and Mary would go to their little cottage in Gwernogie in Carmarthenshire. To their great credit, despite never becoming Welsh speakers, they were able to become integrated into the local community. Fortunately, the local vicar had a great interest in music, and Michael was able to introduce concerts into some of the churches and chapels in the vicinity.

After the unfortunate stroke that forced Michael to retire from the Academy some eight years ago, he and Marymoved to Wales permanently, and it was his determination to return to normal life, and the knowledge of his potential that could still be achieved on the local cultural scene, that proved to be such a help in his remarkable recovery. His speech returned to him and he was available to take on some new pupils, some from as far away as Aberystwyth. He did great things too, for the Carmarthen Arts Club and for the Carmarthen Festival, offering his  wide professional experience and his musical knowledge and expertise to help the Festival shake offitsprevious rather amateur status, and in doing so, making it into the more prestigious event that it has now become. He was even able toplay in a concert or two, but by now he had entrusted the general running of the T.C.O. to his friend and former student, Keith Marshall.

wide professional experience and his musical knowledge and expertise to help the Festival shake offitsprevious rather amateur status, and in doing so, making it into the more prestigious event that it has now become. He was even able toplay in a concert or two, but by now he had entrusted the general running of the T.C.O. to his friend and former student, Keith Marshall.

Michael was both witty and wise, and had a great sense of fun and a very generous nature. He loved helpingyoung people with their problems, and he would - take endless trouble over them-he would refer to his students as "my children". He was also very forward-looking right to the end of his life, which he lived to the full, and I am sure that he must have had in his mind many plans that worn still unfulfilled. He was a remarkable and affectionate man who will be missed by very many of us.